This week surgeons at the University of Chicago found that the strength of a person's ability to identify odors is an eerily excellent predictor of impending death. If and when your sense of smell fades, it seems, your risk of dying within the next five years is several times higher than that of your inviolate friends.

Yesterday BBC, The New York Times, The Guardian, The Economist, and seemingly every other outlet in the world, reported on the work of doctors Jayant Pinto, Martha McClintock, and colleagues─several with some variation on "the nose knows" in the story. Because a lost sense of smell seems to be a more ominous harbinger than even being diagnosed with cancer or heart failure, but there's never a bad time for a little wordplay. The idea is not trivial or terrifying, but it is a little of both. And it's the most existentially challenging story I've ever heard that also involves something called "Sniffin' Sticks."

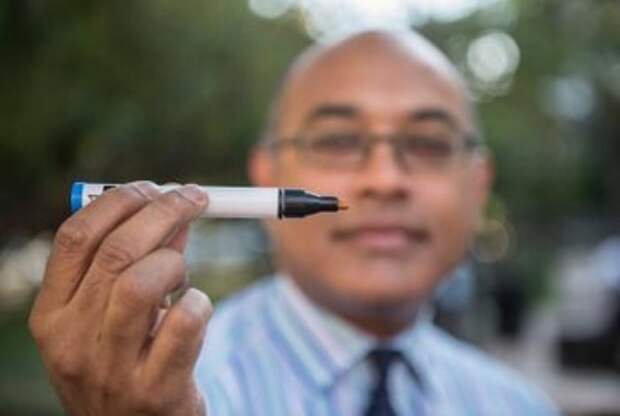

Collaborating between their departments of psychology and surgery, respectively, several years ago McClintock and Pinto created a test of smell that involves aroma-dispensing devices by that morbidly alliterative name. They resemble markers and come in five scents: peppermint, orange, rose, leather, and, everyone's favorite, fish. In an abridged version of a test that doctors regularly use to assess patients who are having olfactory problems, the researchers had more than 3,000 people between ages 57 and 85 do their best to identify each odor. The team then kept track of these people's fates over the ensuing half decade.

Those who got all five scents wrong had a probability of dying during that time that was more than three times higher than people who correctly identified all five. And that was regardless of advanced age, health conditions, mental illness, or any other variable that McClintock and Pinto could think to control for.

And the worst part might be that Pinto and McClintock don't know why this happens.

As Pinto, a specialist in sinus and nasal diseases, explained it to me, "It's unclear."

He told me the important takeaway here is thatdoctors should pay attention to patients' senses of smell as indicators of overall health. He and McClintock even foresee widely implementing this smell test (or some variation thereof) as a quick and cost-effective health-screening practice. If you score poorly, the doctor could then shake his or her head and recommend that you get your affairs in order. No, wait, I mean they could try and find out what's wrong and prevent you from dying.

The olfactory nerve, the sole conduit from a person's nose to their brain, also happens to be the only cranial nerve that is directly exposed to the environment. With that comes exposure to pollutants, viruses, etc. It could be that loss of smell (or, anosmia) is a warning sign of cumulative pollution exposure, Pinto said, which can cause heart and lung disease or cancer. There are also stem cells in the olfactory nerve, so it is constantly regenerating, and that process reaching an end point could be an indicator of the body’s waning overall ability to repair itself. In that sense, as Pinto told me (and wrote in the study itself), losing one's sense of smell is a "canary in the coal mine." Part of the reason that we're left to speculate why this smell-death relationship exists is that the researchers did not track the causes of death in their study. But at least we know it's bad!