In this article, you’ll learn how to prevent shin splints – even though it’s a tricky injury to treat.

For a coach, shin splints are the most frustrating injury because there’s no definitive cause, treatment, or method of prevention.

I previously suffered from shin splints for months so I know how debilitating they can be.

What starts as a minor ache on the side of the shin bone can progress to a throbbing, burning pain that persists for an entire run (and even while you’re just walking around).

The worst part? The most common shin splint treatment – what most runners think works – is completely ineffective.

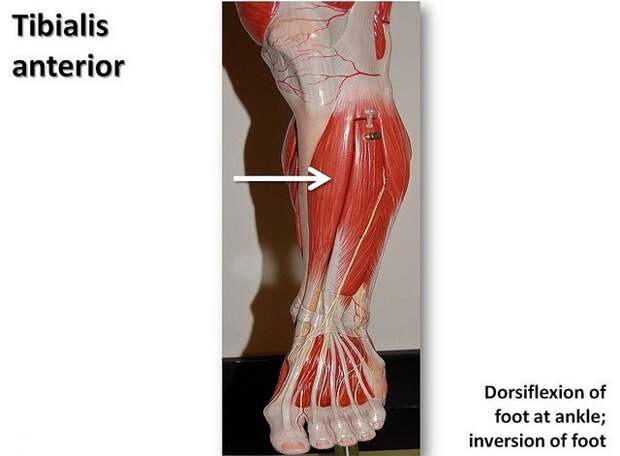

Many runners use a Thera-band to strengthen the shin muscle (typically the tibialis anterior) and prevent shin splints. But strengthening the shin muscle is a waste of time. This treatment strategy is a myth because the role of the tibialis anterior isn’t shock absorption, it’s dorsiflexion of the ankle.

You don’t have shin splints because your shin muscle is weak. You probably have shin splints from training mistakes or other external factors that can be fixed with a better structured training program.

I invited Mike Young to share his expertise on how runners can prevent shin splints with the SR audience today. Mike has a BS in Exercise Physiology, an MS in Coaching Science, and a PhD in Biomechanics. He also has certifications from the National Strength & Conditioning Association, USA Track & Field, and USA Weightlifting.

Mike is also the founder and Director of Sport Performance for Athletic Lab where he serves as the strength and speed coach and the main biomechanist for the facility.

As a world-renowned expert in speed and strength development – and someone who has worked extensively with professional athletes – I’m particularly interested in Mike’s thoughts on the murky prevention and treatment protocols for shin splints.

What Causes Shin Splints?

If weak shin muscles don’t cause shin splints, what does? It might surprise some runners to learn that the shin bone (or Tibia) actually bends during the stance phase of the running gait. Just like a mighty oak tree sways in the wind, your bones are meant to absorb impact and the best way to do that is to bend slightly.

In healthy runners, this poses no problems at all. In fact, this process makes the shins stronger and better able to withstand heavy training, which is the primary reason that shin splints usually affect beginner runners rather than veterans.

With extra impact forces on the tibia from running, new runners should actively work to reduce those impact forces. One of the best ways to do that is to increase cadence (or step rate) to at least 170 steps per minute, but ideally closer to 180. This one simple form upgrade reduces over-striding, aggressive heel-striking, and reduces impact on the tibia.

For more on how to run properly, check out this in-depth guide to running form here.

Instead of directly focusing on the shin muscles, it’s more productive to address the way you train. Mike has this to say:

There are four top causes for shin splits. The first is changing shoe types, where I most frequently see shin splints occur when transitioning to ‘competition’ shoes, whether spikes or flats.

The next problem is failing to change shoes when necessary. Sometimes people wear their shoes well beyond their life cycle which can lead to problems.

Next is running surfaces: I’ve found grass and trails can be useful both because they are so much softer but also the fact that they are irregular is likely to reduce the likelihood of overuse injuries.

Finally, I’ve seen people get shin splits when mileage or intensity increase dramatically. The body simply doesn’t have time to adapt to the greater training load and the weakest link is the first to break… for many people that’s the shins. One of the most overlooked ways that intensity increases is downhill running. Downhill running dramatically increases the impact forces at contact.

As any runner with shin splints intimately knows, running through this injury can be excruciating. It’s critical to know how to differentiate between “normal” soreness and a potential stress fracture or exertional compartment syndrome – both of which are serious injuries.

Mike explains that after about a day, “normal” soreness should progressively improve. But there are outliers:

With more chronic soreness the pain often subsides much more slowly. This is especially true with shin splints which are inflammatory in nature.

Other than perhaps in very beginners, pain in the shins is not a normal outcome of running and certainly not to be considered the same as muscle soreness from a hard training session.

If you’re a beginner, it’s critical to manage shin pain early, aggressively, and thoughtfully with treatment strategies that address the cause of the injury.